Unless you happen to be a Swiss cowherd, there’s a fair chance you’ve never clapped eyes on a real alphorn. It may look like a wonky didgeridoo or a section of bathroom plumbing, but it’s a European national instrument as much loved in its homeland as bagpipes are by the Scots, and after decades in the musical wilderness, its distinctive tones are once again reverberating across idyllic Alpine hillsides.

Alphorns are those comically oversized, pipe-shaped tubes tooted upon by wholesome-looking Swiss folk, usually when surrounded by nodding wildflowers and happy cows. Their sound is like a more mellow tuba, and it’s enough to transport the most jaded urbanite to a place of fresh mountain air, holey cheese and ruddy-cheeked health. That’s going to be me, I reflect, gazing out the window of my train as it hurtles along the startlingly pretty north shore of Lake Geneva toward Montreux. I’ve been invited to come and play the instrument, sit in on a rehearsal and figure out what makes alphorn players tick.

“There was a dream,” the kindly academy founder, Francis Scherly, tells me from his office, surrounded by mementos from his two decades at the cutting edge of alphorn culture. “In 1998, legendary horn player Jozsef Molnar and I discussed creating a school to train a new generation of players. I wasn’t sure it would succeed, but the new technology of the internet allowed us to connect with a strong core of players and it just grew from there.”

Today, there are 95 active members of varying abilities, who study, practise and play concerts, like the main event in Montreux, where an ensemble performance will mark the academy’s 20th anniversary with bucolic alphorn standards against a picture-perfect backdrop. But the academy has ambitions far beyond the shores of lake Geneva.

“Over time, as we grew and became more confident, I developed a Winter Quarters programme,” says Scherly. “Switzerland is too cold in winter, but we always want to play, so I took a chance and booked us off-season concerts in Egypt, Kenya, Marrakech and Tenerife. The alphorn is an outdoor instrument, so to do more of what I love, I simply booked us to play where it’s warm outside.” I’m delighted to learn they’re big in Japan, where the alphorn is wildly popular and the academy – average age just a little over 60 – is off on tour later this year. Lock up your grandmas.

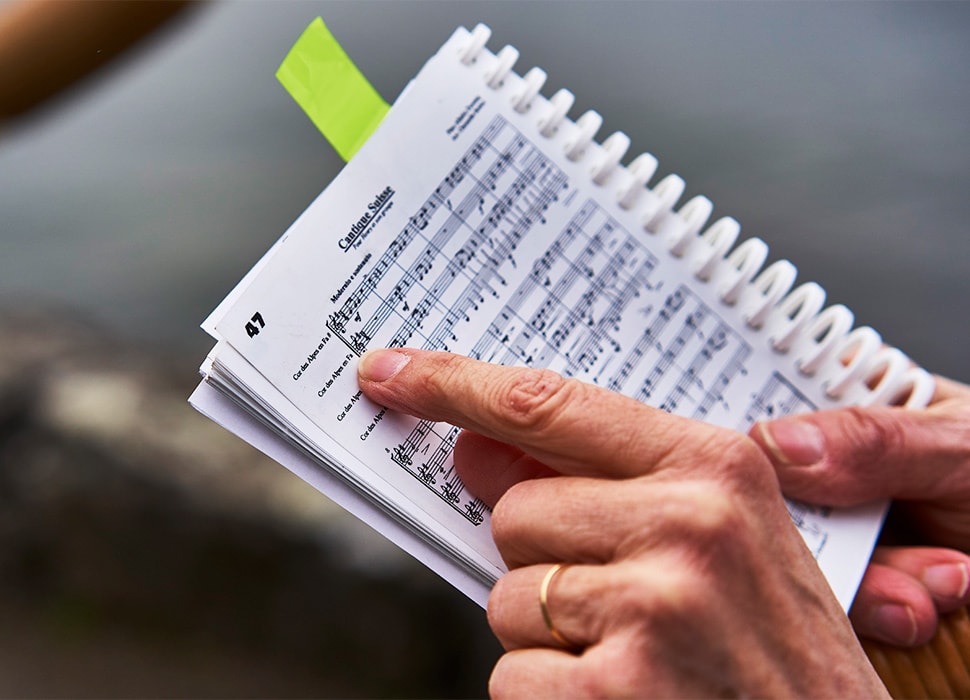

I’m invited to sit in on a rehearsal at a school hall in Villeneuve, a sleepy town at the easternmost point of the lake. Scherly’s spot on: they do sound much better outside. Still, despite the clamour, it’s heartwarming to see 30 amateur performers, all in traditional dress, playing their hearts out. One lady, I’m told, has driven 250km just to participate in the rehearsal. Once everyone has warmed up, we trot out to a patch of grass by the lake and they all blast their horns in unison, a stirring spectacle that couldn’t be more Swiss if it was rendered in chocolate.

Later, back in the hall, we sink a few tumblers of local wine and talk alphorns. “I don’t like tattoos, but I guess you could say the artwork is sort of like a tattoo,” says Beat Studer, banker and alphorn enthusiast, when I ask about the designs painted around the base of most horns. National symbols – in particular, the edelweiss flower – are popular choices, painted directly onto the wood. Just like tattoos, they reflect the personality of the owner and are an irreversible, one-time deal. I’m assured the richness and complexity of designs make zero difference to the beauty of the sound produced, although the Swiss emblem itself is clearly a big plus (boom-tish).

I’m finally driven out to a lakeside spot by Chillon Castle for a blast in the capable hands of alphorn devotee Susanne Wirth Dulex. Because they’re so long – 3.5 metres– alphorns are usually transported in sections, and have to be screwed together, making Wirth Dulex appear, for a brief moment, like a snooker player or a sniper.

She motions me to grasp her horn and give it a good blow. Pursing my lips and gazing out over Lake Geneva to the majestic snow-capped peaks beyond, I feel as I imagine my host’s antecedents have for centuries. Here was my chance, finally, to see if I could cut it as a cow-attracting Alpine artiste. A passing tourist shamelessly grabs a selfie with me. But would I dazzle the esteemed folk of the academy with a rich, resonant tone? Or disgrace myself with a lame, farty misfire? It’s fair to say, alas, I completely blew it.